Sicily - 1943

Operation Husky

World War II: July 10th - August 7th, 1943

BACKGROUND TO THE INVASION

1939-1943: Training in England. Major Hoffmeister leads B Company (sans drummer-boy) on a route march near the village of Limpsfield in the summer of 1940.

Canada declared war against Nazi Germany on September 1939 and against Fascist Italy in June 1940. Over the next five years more than one million men and women volunteered to serve in the Allied campaign to liberate Europe from tyranny. Canadians played a major role in the Battle of the Atlantic, the strategic bomber offensive, and in the land campaigns in Italy and Northwest Europe. Nearly 6,000 of the 42,000 Canadians killed on active service lie buried in Italy.

The Italian Campaign began with the invasion of Sicily on 10 July 1943. The decision to invade the island was made at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. For Winston Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff, Sicily was the first step in a plan to force Italy out of the war and end Nazi dominance in the Mediterranean.

The Americans hoped to limit the campaign to Sicily, preferring instead to concentrate Allied resources for the invasion of France. Although Canadians had no voice in the strategic direction of the war, their request to contribute a division to the Anglo-American forces was accepted by the planners of Operation Husky.

The overall plan called for the Canadians, operating on the left flank of the British 8th Army, to advance towards Enna and then turn east to outflank the German defences concentrated around Mount Etna.

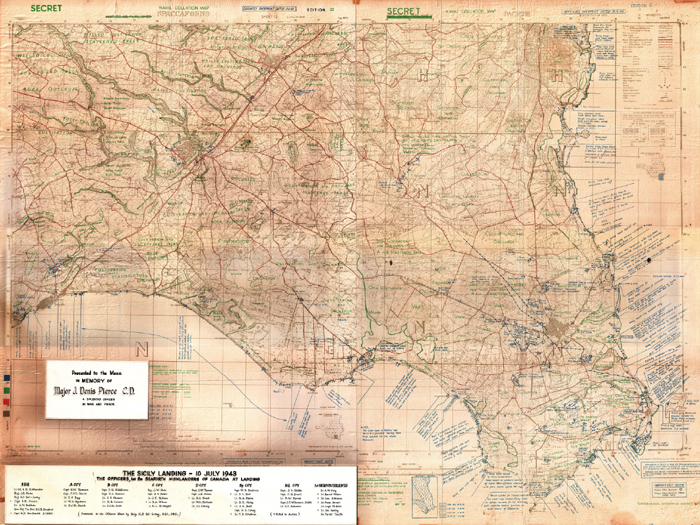

THE LANDING IN SICILY

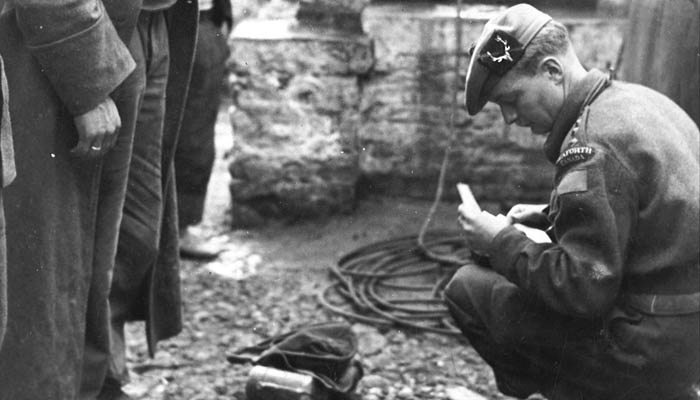

Private Harold Hammond | In an age without personal radios, he has been tasked as a runner to carry messages and orders, and he has been issued a bicycle to make him more efficient.

Left to right: 1939-45 Star, Italy Star (awarded for service in the Sicily and Italy Campaigns), France and Germany Star (awarded for service in the North West Europe Campaign), Defence Medal (for service in the UK during the Battle of Britain), Canadian Volunteer Service Medal (with bar for service overseas), War Medal 1939-1945

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade, under the command of Major-General Guy Simonds, sailed from Great Britain in late June 1943. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada (Seaforths) were in the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade with the Highlanders of Canada Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) and the 49th Edmonton Regiment (Edmontons) under the command of Brigadier Chris Vokes. Bert Hoffmeister who rose through the Seaforth ranks from cadet private to Lieutenant colonel commanded the Seaforths. En route, 58 Canadians were drowned when enemy submarines sank three ships of the assault convoy. Five hundred vehicles and a number of guns were lost. Nevertheless, the Canadians arrived late in the night of July 9 to join the invasion armada of nearly 3,000 Allied ships and landing craft.

Some of the release points were over eight miles from the beaches. There were many natural and man-made hazards once they had landed. There were projected to be at least 8–12 coastal guns, a large Italian garrison, numerous sandbars and deep water near the shore.

Just after dawn on July 10, the seaborne assault (preceded by American airborne landings) went in. Canadian troops went ashore at Costa dell’Ambra (the Amber Coast) near Pachino close to the southern tip of Sicily. The Canadian area was code-named “Bark West” and the Seaforths landed at “Sugar” Beach. They formed the left flank of the five British landings that spread over 60 kilometres of shoreline. The Americans established three more beachheads over another 60 kilometres of the Sicilian coast. In taking Sicily, the Allies aimed, as well, to trap the German and Italian armies and prevent their retreat across the Strait of Messina into Italy. There was good support from naval gunfire into the enemy positions.

When the Seaforths landed there was some confusion as two companies and the HQ element were landed too far to the right on the other side of the PPCLI. In true highland style, the Seaforths landed with the bagpipes playing despite orders to leave their bagpipes with the luggage. The chaos eventually sorted itself out. The Allied Forces were surprised at the lack of resistance and casualties. The Italians were surrendering in droves. Many of them were shoeless, hungry and of poor discipline.

The Canadian author Terry Copp wrote about the German strategy: “The German high command initially classed the Allied invasion as a Dieppe-level raid that would be quickly crushed, but by July 15, Hitler agreed that western Sicily must be abandoned and a new defensive line based on Mount Etna established. The German commander was informed it was important to fight a delaying action. However, no risks were to be taken with the German divisions in Sicily especially “the valuable human material” that was to be saved for the defence of the mainland.” [i]

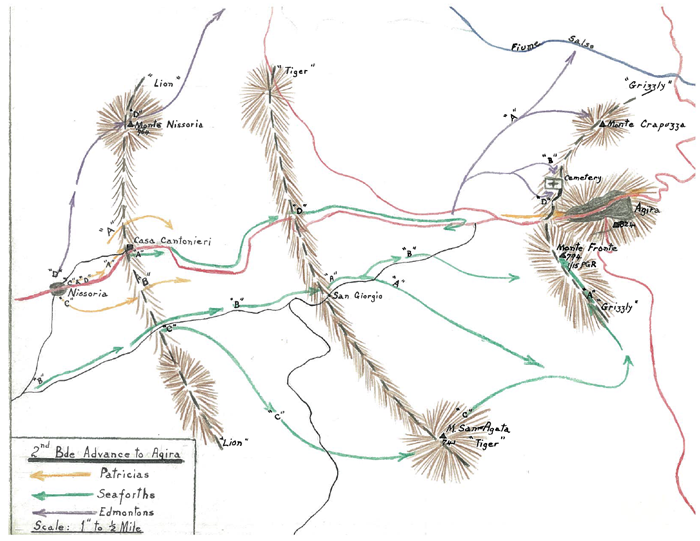

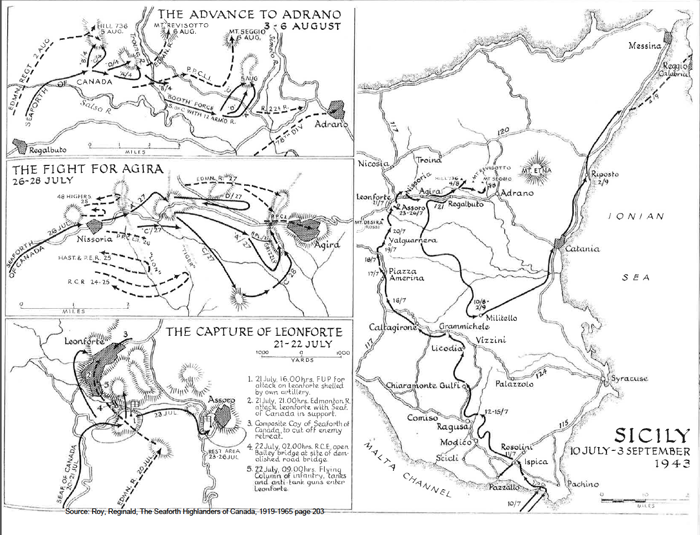

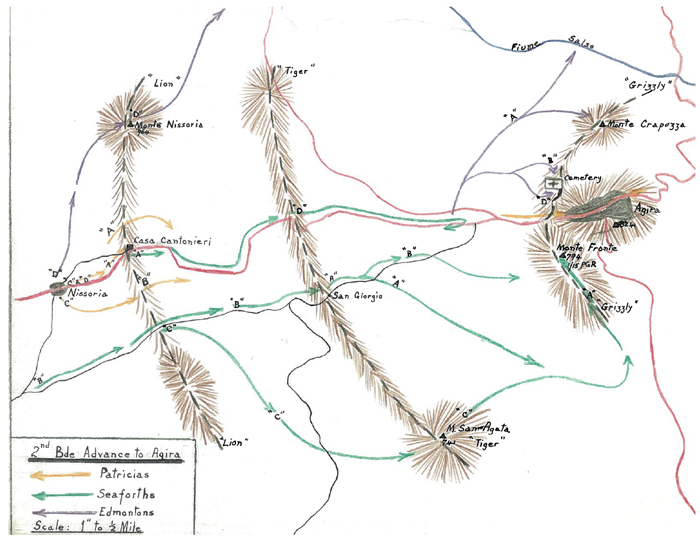

MAPS

THE ADVANCE NORTHWARD

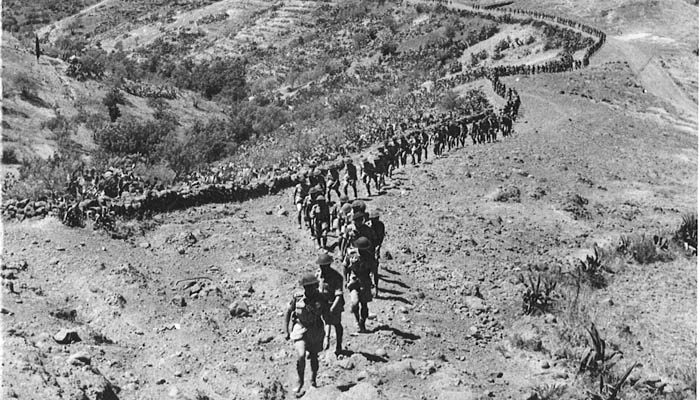

From the Pachino beaches, where resistance from Italian coastal troops was light, the Canadians pushed forward through choking dust, a blistering sun and over tortuous mine-filled roads. At first all went well, but resistance stiffened as the Canadians were engaged increasingly by determined German troops who fought tough delaying actions from the vantage points of towering villages and almost impregnable hill positions.

The Canadians advanced north on foot as the road was either too difficult for vehicles or there were no vehicles to be had. Along the way there were cheering civilians offering them food and wine. However, there was definite lack of water. They also had to contend with hundreds of surrendering Italian soldiers.

On 12 July, the battalion reached Modica after a brief skirmish. From there they pushed on to Ragusa. The Seaforths covered the 30 miles in 24 hours. On 15 July, Vancouver’s highlanders continued to push 50 miles northward to the town of Grammichele. In the next few days, they would march on to Valguarnera. The scenery reminded many men of the Okanagan Valley of BC. [ii] Most of this journey was accomplished on foot but mules carried some of the heavier equipment.

Terry Copp remarked about the terrain of Sicily: “The very rugged country prevented ambitious deployments of troops who had very little pack transport or none. It was admirably suited to infantry tactics, though in the nature of things the attacker toiled up, across, perhaps down to get to grips with an enemy whom often he could not see.” [iii]

A SOLDIER'S NOTEBOOK

LEONFORTE

On the evening of 18/19, July Lt Col. Hoffmeister and the Seaforths were leading the 2nd Brigade to the hill town of Leonforte. Just north of the town, the Seaforths came under heavy machine gun, artillery and mortar fire. It appears that the Germans were waiting to spring an ambush against the whole battalion when they were on the open plain. Luckily, Lt Col. Hoffmeister became suspicious and he sent “A” Company up to a high feature to cover the regiment. This move saved a lot of lives. Nevertheless, the battle lasted most of the morning and the Seaforths suffered 18 casualties.

The Seaforths were getting to Leonforte slowly, but surely. On 20 July, a Seaforth scout force of two platoons pushed into the town. At dawn, the force was detected and it withdrew due to enemy fire from the advantage of the high ground.

Brigadier Vokes confirmed that the Seaforths would assault the town. Unfortunately, due to its location, the town of 20,000 people would have to be attacked frontally. Brigadier Vokes ordered Lt Col Hoffmeister to launch a full-scale attack behind a bombardment fired by the entire divisional artillery. This attempt at demoralizing and disorganizing the defenders required the gunners to plot their targets from a map, a procedure known as predicted fire. Unfortunately, such area shoots were sometimes subject to error due to faulty maps, inadequate meteorological data and other variables. [iv]

On 21 July Lt Col. Hoffmeister held a battalion Orders Group. During the briefing four Canadian artillery shells landed into the building where the meeting was held. Luckily, there were some artillery officers there to call in a cease-fire. This friendly fire incident cost the Seaforths 30 killed and wounded. [v]

Due to these casualties and with a Seaforth company pinned down, Brigadier Volkes decided to send the Edmontons into Leonforte. Nevertheless, the majority of the Seaforths were held in reserve on “Bloody Hill”. A composite company led by Major “Budge” Bell-Irving circled around to the northeast of Leonforte to block an enemy retreat. Nevertheless, the two battalions of the German 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment withdrew eastward. The Seaforths suffered 28 killed in action and 48 wounded in action.

The next few days were spent resting and refitting near Assoro. Leonforte was behind them but it would not be forgotten for a long time. The battalion began to receive reinforcements to plug the holes. [vi]

THE WEAPONS OF OPERATION HUSKY

AGIRA

The next objective was Agira. The assault against Agira began with a three-day battle around Nissoria. Terry Copp wrote on the planning before the assault on Agira: “The planning assumption was that the enemy would hold the hilltop defences around Agira. Little attention was paid to the village of Nissoria, located on low ground along the highway between two low ridges. [vii]An infantry battalion of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, supported by a few tanks and self-propelled guns, had been surprised by the “remarkable athletic accomplishments” of the “British” [Canadian] troops who had appeared “in our backs during the night” at Assoro. They decided to defend Agira using the reverse slopes of the two ridges at Nissoria as the first and second lines of defence. Simond’s plan to use aircraft and field and medium artillery to support 1st Brigade’s move into Agira assumed that a relatively light barrage–lifting 200 metres every two minutes–would be enough to neutralize the enemy and permit the Canadians to close and destroy.” [viii]

The Seaforths would capture Monte Fronte southwest of Agira, which was code named “Grizzly”. The attack was also to be supported by strong artillery support. The battalion formed up near Nissoria and waited the order to advance.

During the evening of 26/27 July Brigadier Vokes sent “A” and “C” companies forward under the cover of darkness. The rest of the battalion would follow their route. The battle became confusing due to the very hilly terrain as all of the hills looked alike, especially in the dark. Other problems were the lack of communications, the well concealed entrenched enemy positions and the single road, which was not very well suited to, wheeled or tracked vehicles.

Soon after the Seaforths advanced, they came under Germans machine gun and “Moaning Minnie” (mortar) fire. Due to the “Fog of War”, the Seaforths ended up on the PPCLI’s objective code-named “Tiger” purely by luck. The PPCLI had also got lost in the “Fog”. There was an enemy tank entrenched on its summit. The Seaforths had PIAT anti-tank guns but the transport mules had bolted with the ammunition. By 1100 hours, “Tiger” was secured with reinforcements.

“C” Company was advancing south of the main road at a slow pace under enemy fire. “D” company was making its way northwest of Agira but it was having a tough time and communications were difficult especially when the signaller was killed. They were soon withdrawn due to the tough German resistance on “Cemetery Hill” which was north of “Grizzly”.

A SOLDIER'S SERVICE & PAY BOOK

OBJECTIVE “GRIZZLY”

The next objective for Major Bell-Irving’s “A” Company was “Grizzly” Hill, which was two miles east of “Tiger” on Monte Fronte. It was a square-topped hill defended by German paratroopers who were well dug in and undaunted by the Canadian shelling. However, the enemy was in no condition to launch a counter-attack. The only available reserve was a fresh battalion from the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. It was brought forward to take over the defence of “Grizzly” while the battered 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment reorganized. The key to the “Grizzly” position, Monte Fronte, was strongly fortified with additional machine guns and mortars. However, the enemy failed to appreciate the determination of Major Bell-Irving and his Seaforth men.

Behind this position was the prize – the town of Agira. Lt Col. Hoffmeister was running around the battlefield ignoring the shell and mortar fire to seek out better positions for his units. At 1400 hours, “A” Company (now reduced to 50 men) advanced to the base of the hill.

Major Bell-Irving halted his attack as he realized that this plan was not working. He left an element in place to distract the Germans while he led the rest of his troops up the south slope. They used the cover of vineyards and orchards to get into the attack position. They then scaled a 300 foot cliff to surprise the enemy. The Germans quickly recovered and a fierce battle ensued. The Germans were throwing everything at the Seaforths there. It was beginning to be a stalemate.

Major Bell-Irving’s “A” Company was defying the Germans to retake the hill. The Germans even did a bayonet attack. This was probably the only bayonet attack inflicted on the Seaforths during the whole war. [ix] It lasted for the rest of the 27th of July and well into the night.

By dawn, the hill was in Seaforth hands. The Company lost two soldiers dead and five wounded. The Germans suffered 75 killed, 15 captured and an unknown number of wounded for their efforts.

After the war, Major Bell-Irving stated, “The protection of the forward line of the Company was a stone wall about two feet high. It was on this occasion . . . that Lt. Harling stood up his full height and threw grenades at the oncoming enemy – one after the other- . . . singing [a Hawaiian song] at the top of his lungs. He, more than any other, was responsible for the successful holding of “Grizzly” Hill.” [x] Lt Col Hoffmeister later said; “by fire, movement and plenty of guts” the Seaforths prevailed. [xi]

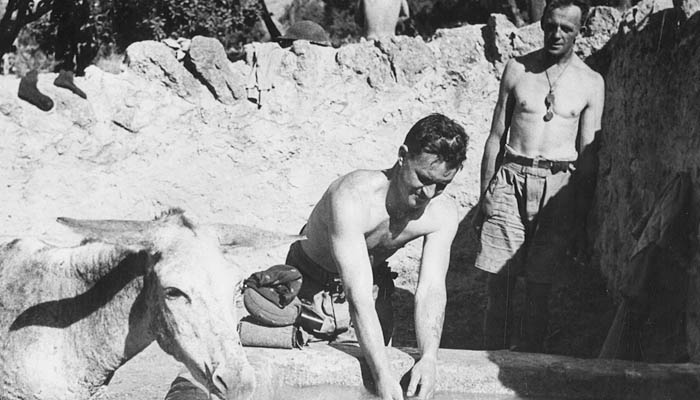

Eventually a company arrived to reinforce “Grizzly”. They came with ammunition but not much water. “A” Company had to do a commando raid to get water from a nearby well covered by the Germans. The water never tasted so good. The aggressiveness and skill displayed during this attack, especially by “A” Company played a major part in the Brigade’s success.

For the Seaforths, the battle was over by the late afternoon. Taking no chances, Simonds arranged for full artillery support for the PPCLI to attack Agira. The PPCLI and the citizens of the town were spared further casualties when an artillery observation officer discovered that the streets to Agira were filled with friendly people anxious to welcome the Canadians. The barrage was cancelled and the PPCLI entered the town as liberators.

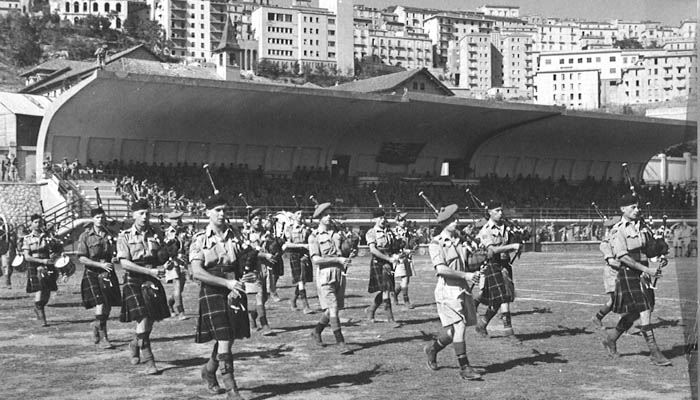

The battle for Agira cost the Canadians 438 casualties, the costliest battle of the Sicilian campaign. In the evening after the battle, Pipe Major Essen and the Regiment’s Pipes and Drums played “retreat” in the town square of Agira. This concert was broadcast around the world on the BBC.

THE PUSH TO ADRANO

On 29 July, the British 79th “Malta” Division began the initial attacks eastward from Agira. They were halted at Regalto. The 2nd Brigade would be used in the hilly country between the Salso and the Troina Rivers. The enemy was forming a block to protect Adrano.

The Canadian task was to break through the main enemy position and capture Adrano. Here, they continued to face not only enemy troops, but also the physical barriers of a rugged, almost trackless country. Mortars, guns, ammunition, and other supplies had to be transported by mule trains. Undaunted, the Canadians advanced steadily against the enemy positions, fighting literally from mountain rock to mountain rock.

The first Seaforth objective was a high hill four miles northeast of Regalbuto. By 0630 hours on 4 August, “A” Company secured a good foothold halfway up the hill. With the help of the tanks of the Three Rivers Regiment, “A” and “C” Companies were on top of the hill by 0930 hours.

Although this objective was secure, they had to wait for their mortars, food and water to catch up to them in the scorching sun. “C” Company was advancing at a slow pace due to heavy enemy fire.

Lt Col Hoffmeister ordered “B” Company to capture a second objective, another high hill 1 ½ miles to the east. It was on the other side of the Troina River. Its seizure would result in the 2nd Brigade dominating one of the two main roads leading north from Adrano. “B” Company sent out a strong patrol and captured it by 1800 hours.

TASK FORCE “BOOTH”

Brigadier Vokes ordered Lt Col Hoffmeister that on 5 August at 0600 hours; the Seaforths would marry up with Lt Col Leslie Booth’s Three Rivers Regiment at the junction of the Troina and Salso Rivers. General Simonds organized an ad hoc battle group of the Three Rivers Tanks, Seaforth infantry, Princess Louise Dragoon Guards scout cars and supporting self-propelled and anti-tank guns all under Lt Col Booth’s command. The tanks could provide closer, more accurate fire support than the artillery and the Seaforths became enthusiastic practitioners of combined arms tactics.

As they waited for the tanks, the Seaforths were eaten alive by mosquitos. The armoured vehicles were delayed by the difficulty of crossing a railroad bridge.

On 5 August Booth's force drove rapidly down the Salso Valley 2 ½ miles to the eastern high ground overlooking the flowing Simeto River. A and C Companies rode into battle on the Sherman tanks. Lt Col Hoffmeister was with Lt Col BOOTH’s tactical HQ.

By 1100 hours the Canadians' wild rush had carried them onto their objective which was held by the seasoned 3rd German Parachute Regiment. The Germans fought hard but the Canadians secured the hill in close quarter battle. The Shermans were used to blast the Germans out of their well-entrenched positions. This was a classic example of exploitation, speed and cooperation. At a cost of 43 Seaforth casualties, the Canadians captured the position. Incidentally, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill watched the battle from the nearby village Centuripe. This was the last battle in Sicily for the Seaforths.

O'Er the HILLS & FAR AWAY...THE CAMPAIGN ENDS

The Germans eventually withdrew to Messina in the northeast corner of the island in order to evacuate their troops to Italy. The German retreat to the mainland was well underway and the final stages of the battle were conducted by British and American troops. By 18 August, all of Sicily was in allied hands.

The advance to Adrano was the last major operation carried out by the Canadians in Sicily. As the German defensive perimeter contracted, the Canadians were squeezed out of the battle and sent into reserve on 7 August. Eleven days later, British and American troops entered Messina. The Allies had conquered Sicily in 38 days.

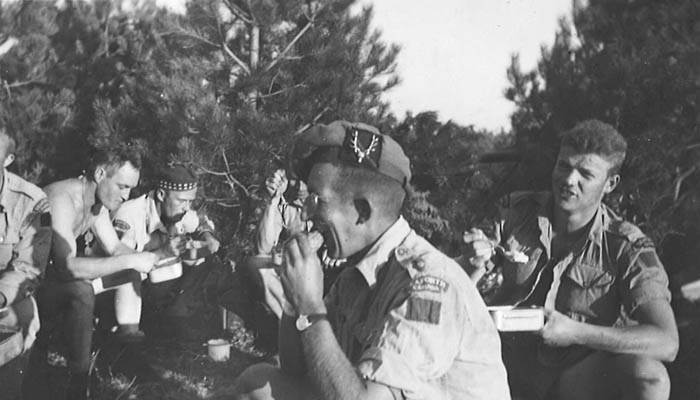

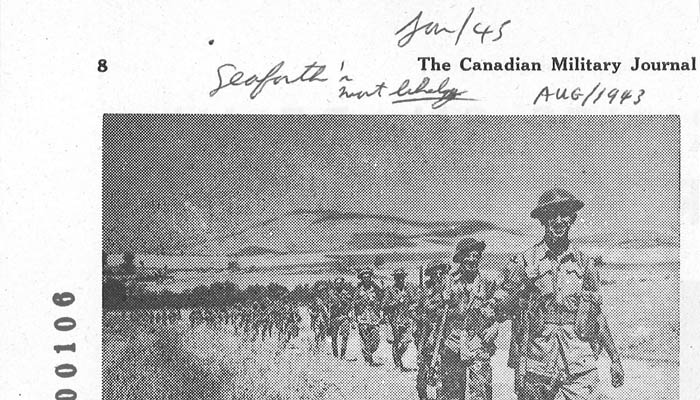

Sicily 1943: the island has been captured, and Lieutenant-Colonel Hoffmeister leads the regiment cross-country to a Brigade Inspection by General Sir Bernard Montgomery

EPILOGUE

The Sicilian campaign was a success although some historians have said that it was a costly victory. Although many enemy troops had managed to retreat across the strait into Italy, the operation had secured a necessary air base from which to support the liberation of mainland Italy. It also freed the Mediterranean Sea lanes and contributed to the downfall of Mussolini, thus allowing Italy to sue for peace.

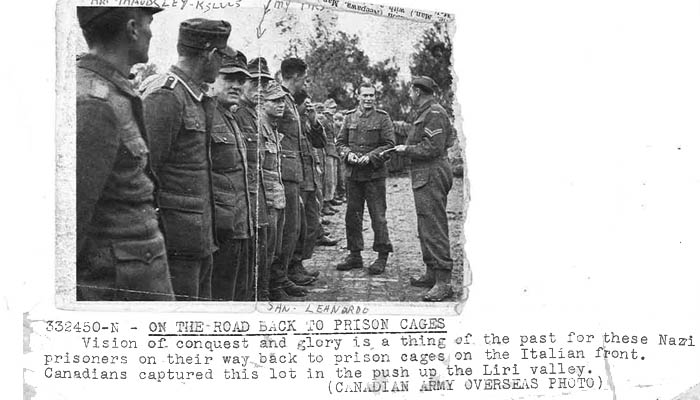

After the Battle of Agira, an English speaking German prisoner had high praise for the Canadians of the 1st Division [who wore a red square badge on their right shoulder]. He told his captor: “We see the Red Devils coming and we fire our mortars hard. But the Red Patches just keep coming through the fire. I can’t understand it. Other troops we fought lay down and took shelter when the mortars fired right on top of them. The Red Patches are Devils.” [xii]

When the smoke cleared, the Seaforths were a different battalion than the one which hit the beaches at the beginning of July. They “emerged as a wiser, harder and more assured group”. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada rested and refitted in an area they called the “Happy Valley”. Unfortunately, much of the concentration area south of Catania was a notorious malaria zone. Despite precautions, hundreds of new cases of malaria surfaced.

For The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada the highlight of this respite from battle was undoubtedly on 25 August, when they held a "reunion" with the 2nd, 5th and 6th Battalions, [Imperial] Seaforth Highlanders at Catania. It was an occasion unique in the Second World War, a similar gathering on a smaller scale having taken place in France in 1918. Ceremonies opened with the massed pipes and drums of the four battalions marching to the Catania Stadium for the sounding of Retreat. It was according to the war diary, "a never to be forgotten sight, that kilted phalanx walking through Catania with local populace agape with wonder and admiration." [xiii]

The Canadians had acquitted themselves well in their first campaign. They had fought through 240 kilometres of mountainous country - farther than any other formation in the British 8th Army. During their final two weeks, they had borne a large share of the fighting on the Allied front. Canadian casualties throughout the fighting totalled 562 killed (including 63 Seaforths), 1,200 wounded (approximately 190 Seaforths) and 84 captured as prisoners of war (3 Seaforths). Several hundred battle exhaustion and malaria casualties were added to this total. One in every four Canadians who fought in Sicily was a war casualty. [xiv]

Sicily was the first real test of what Canada’s citizen army could accomplish in battle and they passed with highest honours. On 3 September, the invasion of the Italian mainland was to be next great operation. There would be many more hard fought battles and glory gained until the Seaforths returned home to Vancouver in October 1945.

A Hero’s Welcome: The return of Vancouver’s infantry regiment was made a city holiday, and thousands came to cheer their “Highland Men” home from the war. The battalion formed up on the parade square to the east of the armoury, a last command was given, and then they all went home. Five years later many of them would be standing on the same parade square, waiting to go to the Korean War...

Two part documentary film by Rai Storia during Operation Husky 2013. There were two people creating documentaries: Max Fraser for Canada and Matteo Berdini for Italy.

Rai Storia is an educational history channel and you can view the first and second part of the documentary in the section called R.A.M. at the following links:

Part One

Part Two

APPENDIX

War Diaries - July 1943 (Intelligence Report)

War Diaries - August 1943 (Intelligence Report)

War Diaries - September 1943 (Intelligence Report)

Official History of the Canadian Army in WW II, Vol II (Sicily Extract)

Legion Magazine - From Leonforte to Agira

Legion Magazine - Taking the Rough Land of Sicily

Legion Magazine - Beginning the Battle for Sicily

[i] Copp, Terry. “Beginning the Battle for Sicily.” Legion Magazine, September 2005.

[ii] Roy, R.H. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada 1919-1965. Vancouver: The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, 1969.

[iii] Copp, Terry. “Taking the Rough Land of Sicily.” Legion Magazine, January 2006

[iv] Copp, Terry. “From Leonforte to Agira.” Legion Magazine, November2005

[v] Dancocks, Daniel G. The D-Day Dodgers: The Canadians in Italy, 1943-45. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991.

[vi] Roy, R.H. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada 1919-1965. Vancouver: The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, 1969.

[vii] Copp, Terry. “From Leonforte to Agira.” Legion Magazine, November2005

[viii] Copp, Terry. “From Leonforte to Agira.” Legion Magazine, November2005

[ix] Roy, R.H. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada 1919-1965. Vancouver: The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, 1969.

[x] Roy, R.H. The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada 1919-1965. Vancouver: The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, 1969.

[xi] Dancocks, Daniel G. The D-Day Dodgers: The Canadians in Italy, 1943-45. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991.

[xii] Dancocks, Daniel G. The D-Day Dodgers: The Canadians in Italy, 1943-45. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1991.

[xiii] War Diary, The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, August 1943, Appendix: The Seaforth Reunion 25 August 1943.

[xiv] Copp, Terry. “Taking the Rough Land of Sicily.” Legion Magazine, January 2006